Jacqueline Ross, RN, PhD, Coding Director, Department of Patient Safety and Risk Management

Over the past decade, there has been an increase in the volume of screening and diagnostic procedures in ambulatory endoscopy units (AEUs). Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death from cancer in the United States. This cancer equally affects both genders. African Americans are at a higher risk for colon cancer, as are those individuals with a family history of colon cancer (ASGE Understanding Colon Cancer Screening). As the volume of procedures increases, there is the possibility of increased adverse events. The focus on how to prevent patient harm should be a primary goal. With its mission to advance, protect and reward the practice of good medicine, The Doctors Company (TDC) analyzes malpractice claims to better appreciate what motivates patients and their families to pursue claims and better comprehend system failures and processes that result in patient harm. Malpractice claims provide a retrospective review of care. Information obtained from malpractice claims could be used to design risk mitigation strategies to improve patient safety and reduce malpractice risk.

The aim of this study was to analyze closed medical malpractice claims associated with adverse events associated with endoscopic procedures done in AEUs.

Questions evaluated in this study include:

- What were the common allegations occurring in medical malpractice claims among endoscopists in AEUs?

- What were common injuries in medical malpractice claims among endoscopists in AEUs?

- What were the procedures involved most frequently in medical malpractice claims among endoscopists in AEUs?

- What contributing factors were associated with the most common allegations and procedures involved in medical malpractice claims among endoscopists in AEUs?

- Were there any regional differences involved among endoscopists in AEUs?

- Were there possible differences in medical malpractice claims among gastroenterologists practicing in AEUs participating in the Endoscopic Unit Recognition Program (EURP) compared to those endoscopists practicing in in AEUs not participating in the EURP?

This was a retrospective, descriptive study using closed medical malpractice claims from TDC and Health Risk Advisors (HRA) from the loss years of 2010-2020. Claims from TDC and HRA are reviewed by trained patient safety analysts who use an evidence-based taxonomy.1 Each reviewed claim is entered into a database. The quality of the database is checked both internally and externally. Previous studies have used this database. Only claims involving endoscopists in AEUs were included. Other variables included severity of injury; major and other injuries; contributing factors; allegations; comorbidities; age and gender of the patient; final diagnosis; procedure involved; device if applicable; indemnity and expenses; state the claim occurred; and EURP. The variable of race was not available in this dataset. Descriptive statistics were used.

| 157 closed malpractice claims | |

|---|

| Gender | |

| Males | 46% |

| Females | 54% |

| Age | |

| Average Age (23-96 years old) | 60.09 years old |

| Top Comorbidities | |

| Obesity | 22% |

| Smoking (past/present) | 15% |

| Diabetes | 15% |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 11% |

| Hypertension | 11% |

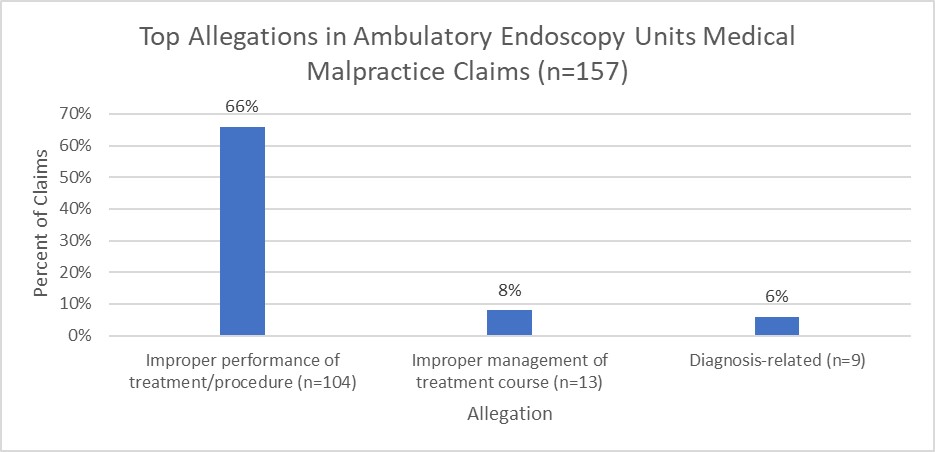

Allegations (Case Types) seen inMedical Malpractice Claims in Ambulatory Endoscopy Units

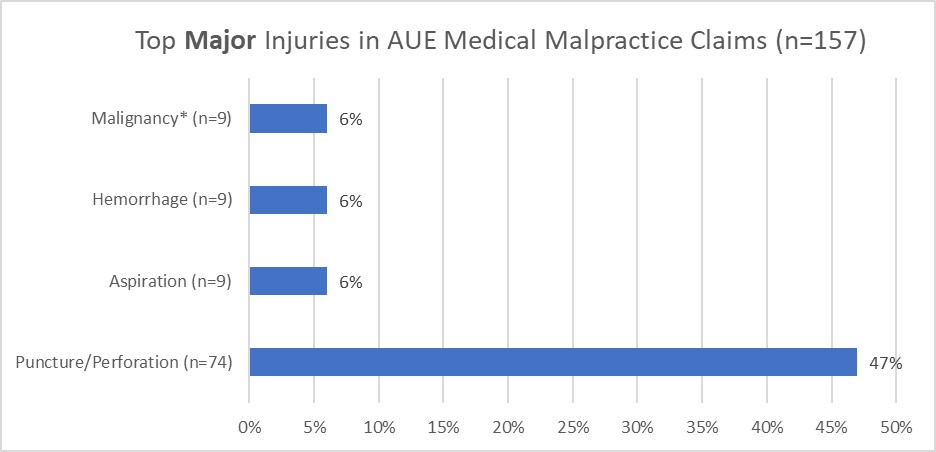

Injuries seen in Medical Malpractice Claims in Ambulatory Endoscopy Units

*Malignancy seen as major injury in diagnosis allegations.

The top major injury in the ambulatory endoscopy unit was a puncture or perforation, with the colon being the most common site, followed by the esophagus. Aspiration, hemorrhage and malignancy were the second most common major injury seen in the endoscopy units. The injury of malignancy was seen only with the claims associated with the diagnosis-related allegations (case-types).

Case Example:

A male patient in his late 60s came to the physician complaining of difficulty swallowing. He also had a history of increasing gastric reflex. A plan was made for an upper endoscopy with a possible dilation of the esophagus. A printed informed consent that contained the risks of the procedure was provided to the patient.

About two weeks later the patient came to the AEU for the upper endoscopy. An informed consent was also signed for the endoscopy unit. The upper endoscopy began. The physician found low-grade narrowing Schatzki Ring (SR) at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). He placed a guidewire and the scope was removed. Dilation was done with 18 mm savory dilatory. The physician documented that normal resistance was encountered. The post dilation exam showed a mucosal tear in the mid esophagus, but it did not appear to be a complete perforation, and the GEJ had successful deconstruction of the SR. There was no crepitus noted. The patient’s vital signs had remained stable during the procedure.

The patient woke up complaining of difficulty breathing and had severe pain in his side and back. The physician was concerned about a perforation. The patient was transferred within 10 minutes to the emergency department (ED). In the ED, a chest X-ray showed perforation of the esophagus with a hydropneumothorax. The patient was transferred to a tertiary hospital, seen by a thoracic surgeon and taken to surgery. The patient had a full-thickness 7 mm perforation from the aortic arch to below the inferior pulmonary vein, as well as 500-700cc of blood in the left chest region. The esophageal perforation was repaired, and a pedicle intercostal muscle flap was placed. The patient had several more procedures and now has post thoracotomy pain syndrome. The outcome of this claim was a defense verdict.

Takeaways: This case highlighted a quick response to a suspected perforation. The patient was transferred in a timely manner to the ED and the perforation was diagnosed. This was a larger than usual perforation, although several experts noted that this injury has been seen in the absence of negligence.

Each claim can contain up to three other injuries. Almost half of the claims (46%; n=71) involved the “other” injury of the need for an additional procedure or surgery. Twenty-two percent of the claimants (n=34) required hospitalization from their injury and another 19% of the claimants (n=29) died because of their injury. Ten percent (n=15) of the claimants developed sepsis.

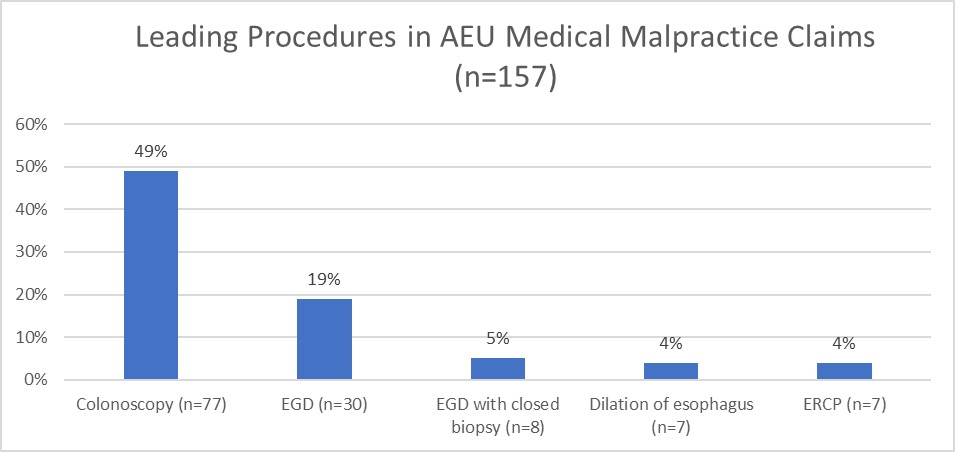

Procedures Done in Medical Malpractice Claims in Ambulatory Endoscopy Units

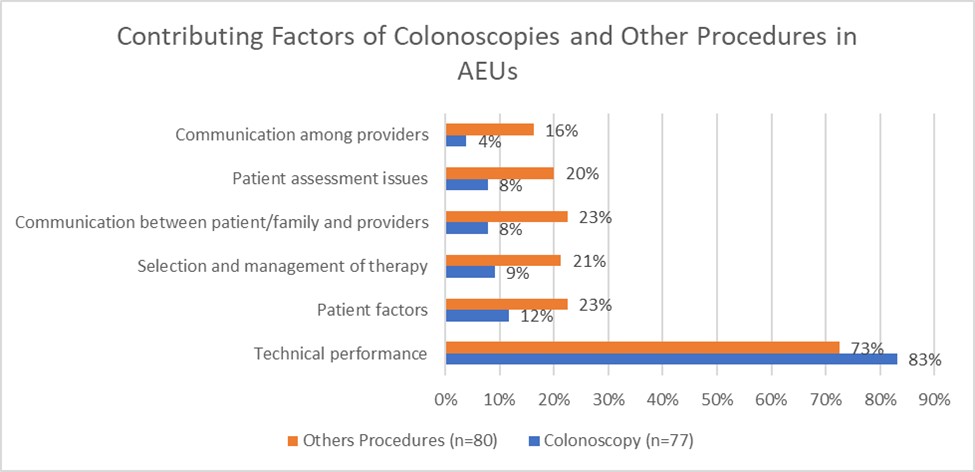

Comparing Contributing Factors Related to Colonoscopies Against Other Procedures in AEUs

One question in the study aimed to identify factors contributing to malpractice claims in the AEU related to the most common procedure performed in the AEU, colonoscopy, compared to other procedures performed in the AEU. With the endoscopists, technical skill was the most common factor associated with adverse events in all AEU procedures. Adverse events occurred most frequently with colonoscopy.

However, in procedures other than colonoscopy, there were higher percentages of contributing factors in every category besides technical skill (See the chart below.). Interestingly, the rankings tended not to differ much from colonoscopy, just the frequency. Communication both with the patient (23%) and between providers (16%) occurred more often with other procedures than with colonoscopy (8% and 4%). Additionally, patient assessment (20%) and selection and management of therapy (21%) were noted to be more frequent factors in the claims involving other procedures in the AEUs than those claims with colonoscopies (8% and 9%).

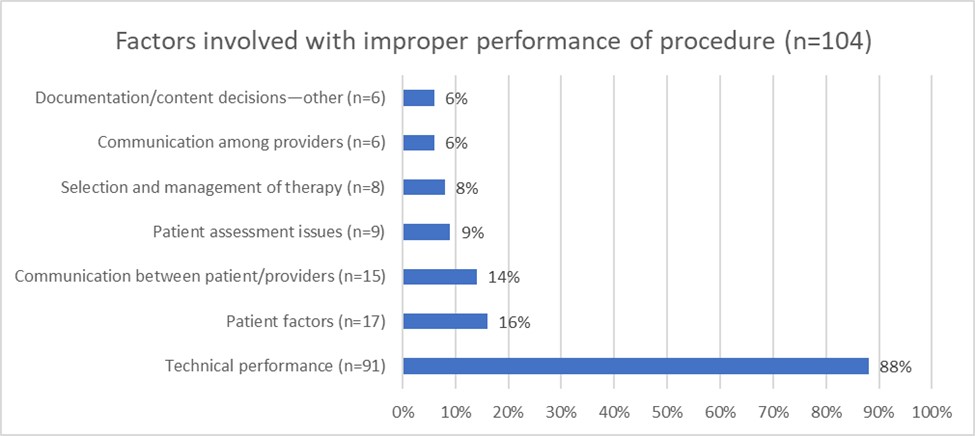

Contributing Factors Related to the Most Common Case Type/Allegation in Medical Malpractice Claims in AEUs

Most malpractice claims occurring in the AEU involved problems related to improper performance of the procedure. This case type often involves various technical skills, such as medication errors, retained foreign bodies, improperly used equipment or technical performance. Technical performance can entail a variety of issues, including improper use of traction, inexperience with a procedure, misidentification of an anatomical procedure, poor technique or known complications of procedures. Known complications of surgical procedures, those reviewed during informed consent, are the most common contributing factors seen with improper performance of a procedure. The following example highlights several contributing factors involved in a claim:

A morbidly obese (BMI 37) female patient in her late 50s with obstructive sleep apnea, smoking and hypertension, presented to the gastroenterologist for a screening colonoscopy. The gastroenterologist planned to do the procedure as an outpatient with IV sedation by a registered nurse. The physician classified the patient as an ASAII. At 8:34 am, her blood pressure (BP) was 114/86. There was no oxygen (O2) saturation documented. At 8:36 am, the nurse administered 5mg IV versed and 100mcg IV fentanyl per order of the gastroenterologist. The nurse documented the sedation as deep. At 8:37 am, the patient’s BP was 135/77; heart rate (HR) 80; O2 saturation 85%. At 8:40 am, the patient’s vitals were HR 39; BP 100/46; O2 saturation 77%. At 8:47 am, the patient was placed on 10L of oxygen. The O2 saturation was not documented on the vital signs, but the saturation was documented in the narrative as being 40%. There was no BP documented, but the HR was at 57. At 8:48 am, the nurse gave 0.4mg Narcan IV and placed an oral airway. At 8:49 am, 500cc of normal saline was started and 0.8mg romazicon IV was given. The patient was noted to be pulseless, and CPR was started. At 8:50 am, epi 1mg IV was given. At 8:51 am, the BP was 104/73. There was no oxygen saturation documented. The printout from the code listed the EKG as “searching.”

At 8:56 am, the EMS arrived at the endoscopy center, and they attempted to secure the airway. An LMA was attempted twice. At 9:01 am, the patient’s heart rate was 133 and BP 84/49. The O2 saturation was 56%. The code was listed to be in progress for 30 minutes prior to transport to ER. The patient was unresponsive when they arrived in the ED. The patient was admitted to the ICU. The EEG showed diffuse changes that were consistent with anoxic brain injury. The diagnosis of hypoxemic brain damage and respiratory failure was made. Hypothermic treatment was started. The family decided to remove life support the following day.

Takeaways: In this claim, the nurse administered the conscious sedation too quickly and placed the patient into deep sedation. This sedation level exceeded IV sedation that should be administered by an RN. IV sedation needs to be given by health care professionals who are experienced and trained with IV sedation. Additionally, this patient had comorbidities of obesity and obstructive sleep apnea, so there were questions about whether this patient should have been sedated by an RN rather than a CRNA or an anesthesiologist. This was a decision made by the physician.

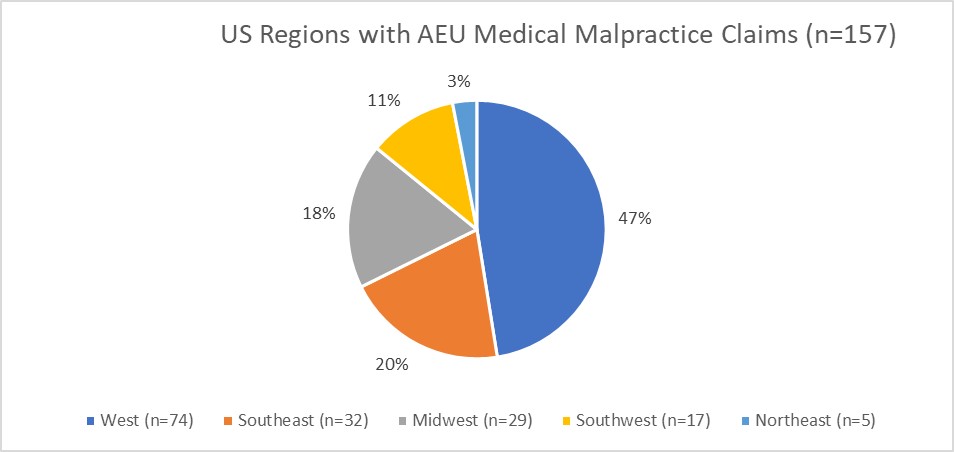

Regional Differences Seen in Medical Malpractice Claims in AEUs

TDC offers malpractice insurance to providers across the country. Understanding if there may be possible regional differences in medical malpractice claims is important. Regions of the U.S. are grouped into five categories: Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest and West. The overall percentage of TDC-insured gastroenterologists by region included 36.3% in the Southeast region, 29.8% in the West region, 18.4% in the Southwest region, 12.5% in the Midwest region and only 3% in the Northeast region.2

The West region had the largest percentage of AEU medical malpractice claims (n=74), while the Northeast had the least (n=5). In each region, most of the claims involved colonoscopy. The Southeast had the highest rate of claims (70%; n=22) associated with colonoscopy. The Midwest had the lowest percentage of claims associated with colonoscopy, 43% (n=12).

The Northeast states would include Pennsylvania; New Jersey; New York; Connecticut; Rhode Island; Maine; Massachusetts; Vermont; New Hampshire. The Southeast region would include Arkansas; Louisiana; Mississippi; Alabama; Georgia; Florida; Maryland; South Carolina; North Carolina; Tennessee; West Virginia; Virginia; Kentucky; Delaware. The Midwest region would include North Dakota; South Dakota; Nebraska; Kansas; Wisconsin; Michigan; Ohio; Iowa; Minnesota; Missouri; Illinois; Indiana. The West region would include Washington; Oregon; Nevada; California; Utah; Hawaii; Alaska, Wyoming, Montana; Idaho; Colorado. The Southwest region would include Arizona; New Mexico; Oklahoma; Texas.

Differences in Medical Malpractice Claims in AEUs Participating in the EURP Compared to Malpractice Claims Occurring in AEUs not Participating in the EURP

TDC provides medical malpractice to physicians who work in endoscopic units with the EURP designation.3 The EURP designation represents a high-quality GI unit (EURP). After cross-referencing EURP units and physicians with the medical malpractice claims included in this study, there were no medical malpractice claims included in this study associated with any EURP physicians insured with TDC.

Discussion

Improper performance of a procedure was the most common allegation, or case type seen in AEU malpractice claims. Improper performance of a procedure would include the various technical steps that the physician does during the procedure. Perforations were the most common adverse event, occurring most frequently in the colon. However, if the allegation involved a missed diagnosis, like colon cancer, then the major injury was a malignancy. The procedure most likely to be involved in a medical malpractice claim was colonoscopy.

Problems related to technical skill was the most common factor when improper performance of the procedure was cited as the allegation. A known complication from the procedure was a common finding, which underscores the importance of a thorough patient-centered informed consent process. This process permits the patient to ask questions, hear all alternatives, obtain information and make an informed decision.4 Each consent should be focused on the specific procedure, and especially in more complex procedure like ERCPs.4 Providers should document the informed consent discussion.

Claims involving colonoscopy were the most common type of claims in this study and were heavily influenced by technical contributing factors. However, in procedures other than colonoscopy in AEUs, contributing factors beyond technical skills were more frequently seen. These other contributing factors included deficiencies in communication and patient assessment. While colonoscopy had lower factors in these areas, the other procedures had larger percentages, indicating more attention may be needed with these procedures.

Almost one in four of the other procedures had an issue with communication between the health care provider and patient/family. Pre-procedure phone checklists can be used to assure important information is conveyed, such as extra precautions for patients with diabetes and concerns for those on aspirin, diuretics, and anticoagulants.

Contributing factors are the selection and management of procedures were seen in 21% of other procedures and 9% of colonoscopy procedures. The documentation of the indication for the endoscopic procedure needs to be included in the medical record. One recommendation4 is to complete a risk assessment for sedation-related adverse events. The use of commonly used scoring systems, like the ASA score and the Mallampati score, is proposed for stratifying risk before endoscopic procedures. 4

Additionally, patient factors contributed to malpractice claims. These are patient-related, that are mostly beyond the control of the health care provider, such as nonadherence to medication or treatment regimen. Patient-related factors could indicate the need to increase attention to patient safety and other patient-related factors.

Several claims involved a delayed diagnosis of a perforation following a colonoscopy. A more focused study on these claims would be of interest. What are the factors involved in the delay? Is the delay related to a post-polypectomy? Do comorbidities, such as obesity or adhesions, increase the risks of delayed diagnosis?

Regional differences were found in this study. However, the reason for this difference was not easy to extrapolate. While we can examine the number of insured gastroenterologists based on U.S. region, this study focused on AEUs, not in-hospital settings. Some physicians may only practice at hospital-based facilities, and some regions may have more ambulatory-based facilities than others.

Limitations

These data were retrospective and used closed malpractice claims from a large national malpractice carrier. Only endoscopists were included in this study. This study did not represent complications that arose in patients who did not file a claim or patients who did not experience complications from their endoscopic procedures.

The ability to differentiate between screening and diagnostic colonoscopies was not possible with the current data. Additionally, this study did not include procedures done in inpatient endoscopic units.

Sources:

- CRICO Clinical Coding Taxonomy; V4.0 2021

- TDC Actuary 2022.

- ASGE. (2020) Endoscopy Unit Recognition Program. ASGE | Endoscopy Unit Recognition Program (EURP)

- Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators common to all GI endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81(1):3-16.